State of the Dao

Chinese Contemporary Art

|

Introduction by Patricia Karetzky |

|

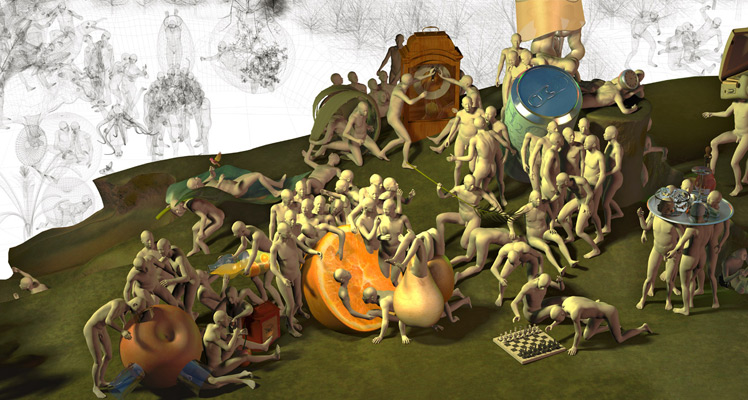

The state of the Dao in contemporary China is in disrepair and some artists are seeking to restore the balance. In this way they are fulfilling the ancient function of the artist in society. Such ideas are inherent in the poetic renditions of the Daodejing ascribed to the hand of Laozi who lived around sixth century bce. This beloved work was as much a blueprint for utopian society as a guide to self-cultivation. Government, it explains, should not interfere in its citizens’ life: left alone society, will find a peaceful coexistence; laws make criminals. In early imperial China Daoists presented copies of the text to emperors to enlighten them and they continued to do so throughout subsequent dynasties. For the text explains, The best rulers are scarcely known by their The teachings promote a government principle that works in concert with the forces of nature-the Dao. This type of philosophy can also be applied to self-government: Empty the Self completely Zhuangzi is the most beloved of the Daoist writers. Living in the third century bce his words still have the power to startle and charm. One of his most frequently cited verses relates a dream: In another verse, Zhuanzi explains the value of living one’s life in concert with the Dao using the most mundane imagery Nearly a thousand years later, these traditions were still vital for artists. The parable of the Peach Blossom Spring, the subject of a fifth century narrative poem by Dao Yuanming is a constant source of inspiration. The poem tells of a fisherman who came upon a hidden community living happily by a peach blossom spring. Rejecting the villagers’ offer to stay and live among them, the fisherman leaves, but just before he departs villagers besiege him to not reveal their whereabouts; but the treacherous fisherman immediately reports them to the local government, who despite their efforts, could not find the village. What is it about humankind that cannot tolerate peace and tranquility? In another tradition associated with Daoism, artists communicate with the spirit world on behalf of society: bedecked in flowers, shamans in ancient China sang songs, performed dances, and offered gifts to the gods to assure peace and harmony. Early on Buddhists and Confucians appropriated the word Dao, or the way, to expresses the ineffable truth, the path of self-realization, and more. By the twelfth century, philosophical thinkers saw a synergy in these three ways of thought and created a new school, San jiao or the three teachings, which combined the three into one teaching. The term Dao then has a very broad meaning that can generally be understood as the Truth or way to the Truth. Faced with the current situation in China, artists are reacquainting themselves with the great literature that was forbidden during the Cultural Revolution; they are amazed and delighted by it, and comforted that they are now able to have access to this special kind of wisdom couched in witty and poetic terms. Inspired by such ancient philosophical writings they draw upon these ideas to understand their world, and some artists today have even resumed their traditional function. They take up themes in their art that reflect the current situation in China; they are acting as intermediaries in the cause of the populace and trying to establish a society in harmony with the ancient principles that propound compassion and independence. The powerful paintings of Yang Jinsong (www.yangjinsong.com) employ a number of themes that illustrate the corruption and pollution of everyday life in China. For example one of his series focuses on an incongruous old over-stuffed sofa from an earlier time. In fact the chair resembles the famous one upon which Mao sits in his state portraits. Covering the disheveled chair, which occupies nearly the entire canvas, is the debris of modern society, the result of planned obsolescence, consumerism, pollution, and military expansion. The ironic coupling of the images suggests the wit of Daoist language, which seeks through jarring juxtapositions to question the nature of human folly. In this case homey comfort pairs with the waste products of modern society whose rubbish accumulates more each day. In his fish series, Yang painted on a blank untreated canvas a great dead silver carp, its eviscerated body revealing bloody innards. Yang explained, the fish is a multivalent symbol representing the natural resources of China, among other things. For this exhibition, Yang’s painting is from his new series based on watermelons, the ubiquitous image of summer in China: at the center of the canvas, the heroic watermelon is split open to reveal the discarded products of our consumer society–computer lap tops, TVs, cell phones, and cosmetics. Placed front and center, dominating the canvas and treated as icons, such images are personal symbols of Chinese society, and it is not only the narrative details that convey Yang’s sentiments. Yang’s style of applying the paint seems akin to abstract expressionism, conveying his emotion, his inner heart, in the dynamic gestures of his brush. But precedent for this kind of brush play can also be found in the dancing lines of Chinese calligraphy–the rhythmic speed and force of the brush embodies the artist’s state of mind. Seen up close, Yang’s brush slashes with great momentum, applying swathes of thick paint in great bold strokes, in this way the technique also conveys the message. This dramatic action painting recalls the Daoist spirit mediums who in a trance convey through their inspired calligraphy the hidden message of the universe. Moreover, close observation of Yang’s canvases reveals delicate passages of lyrical lines dancing about each other in a manner resembling Ch’an (Zen) calligraphy. Yang’s largely monochromatic palette also alludes to Chinese writing. The Gao Brothers (Gao Zhen and Gao Qiang) have pursued a number of different types of artistic expression. Together they have presented a variety of installations, performances and photographic projects. Their on-going series, Utopia of a Hug, is played out all over the world, as strangers are gathered together and enjoined to embrace each other. The performances are photographed and made available on their website (www.gaobrothers.net). This act of affirmation of affection for one another is problematic in China and elsewhere where there is a reluctance not only to demonstrate any physical affection in public but also to physically engage with strangers. The photos documenting the performances reveal a wide range of responses from discomfort to a kind of euphoria. In China some of these performances were held in one of the thousands of unfinished skyscrapers. Friends, artists, itinerant laborers and prostitutes as well as passersby joined together for the event. In a later stage the brothers took the images and manipulated them in a computer making a kaleidoscopic panorama that resembles a mandala. Lately, the Gao brothers have a decidedly more pointed kind of artistic production, exemplified by the series of large-scale polychrome sculptures of Ms Mao, which satirize the cult of the Beloved Leader. Here the icon has large breasts, a Pinocchio nose, and long Chinese braid down her back – mocking Manchu imperialism which imposed the pigtail on the Chinese, the dishonesty of Mao’s reign, and the new sellout to western commercialization signified by the adoption of the Minnie Mouse character and the current craze in China for cartoon characters that decorate all manner of trashy consumer products. For this exhibition the Gao Brothers have a remarkable photo that returns to the idea of the hug series as it records a performance in one of the many construction projects in Beijing. Inhabiting the un-built structure, crowds of figures interact, but the imagery has become more strident. Look carefully and you will see a montage of figures interjected into the photo- a toppling statue of Mao, a raging fire, crimes being committed, bodies lying on the ground bleeding; Osama Bin Ladin clad only in underwear sits in a great comfy chair drinking beer, the Olympic flag flies, acrobats tumble, blind men walk with canes among the chaos of sports cars, trucks, and bicycles; the whole of the human comedy is here in this diary of events in modern China. In 2009 the brothers turned their attention to the problem of prostitution and the abuse of the authorities–they painted a series of works based on internet photos posted by a policeman in an attempt to blackmail the young working girls. The photos reveal the moment of the discovery: the officer, finding the offenders seated in a car, in a hotel room, and elsewhere, shines his flashlight to illuminate the crime; the subjects cringe in the harsh light. Lately the brothers have taken to making art that is more critical of the authorities. This is a secret art, one that cannot be shown in China where there is no right to completely free expression. Xu Yong has made the problem of the single-minded destruction of the architecture of ancient China his own. As silent testimony of life in traditional China, the beloved hutongs have been systematically dismantled to make way for more shopping malls and towering apartment villages. Hutongs are the old neighborhood courtyards surrounded on three sides by low brick buildings enclosed by a wall and entered through a large and impressive gate. Once elegant and refined residences, the hutong have been subjected to a century of dramatic changes that began at the end of the nineteenth century. In these enclosures one lived life among neighbors, found intimacy and no doubt dissension, a kind of life that stands in contrast to the isolation and alienation for inhabitants in the new towers. In a brilliant stratagem to protect the hutong, in the 80s Xu convinced the government to allow tours of the old quarters, which was in direct contradiction to the existing policy of the government that only wanted to showcase the new and Westernized neighborhoods to foreigners and to strictly avoid any site that lacked the shiny patina of modernity. Foreigners, Xu explained to the powers that determined such activities, wanted to see the “real” China, not just the sanitized, polished version with which they were only too familiar in their own countries. Only after years of campaigning and arguing that only by seeing such pre-modern sites could foreigners appreciate the progress China had made were his tours of the hutong deemed legal. Thus, Xu Yong’s hutong bus tours began in 1994, and having been advertised in the western media, they have thrived for nearly two decades and remain in popular demand. One result of this project was the preservation of some hutong. For this exhibit Xu Yong has provided his black and white elegiac pictures capturing the ancient communities before their destruction. In the series 101 Portraits of Hutong from 1990, he captures the ephemeral beauty of the old lanes washed by rain, or the Lamist temple rising over the snow covered entry to the compounds. These photographic records, for Xu, are a memory of the lost past. In his efforts to keep them alive one can see a commitment to Daoist ideals. In August 2002 Xu documented the impact of the destruction on the inhabitants of Xiaofangjya Hutong in Beijing that was demolished two and half month later. Pictures record each of the residents of a household holding a card inscribed with their name and occupation. The community has been destroyed, for little recompense, especially considering the great value of the land. Xu Yong is also the creator of 798 Space in the Dashanzi district of Beijing. In 2002, after learning of the government’s decision to destroy a factory building designed by East German architects in the early 1950s, Xu Yong rented the large industrial space and transformed it into a gallery; he also opened a second gallery for photography and a café. Other art galleries, restaurants, and boutiques soon followed making 798 a thriving commercial art district. Longbin Chen fashions large-scale sculptures out of the cultural debris of our information society. Chen’s paper sculptures are inextricably tied to issues central to contemporary society: discarded reading materials–out-of-date books, newspapers, magazines, and computer paper that are transformed with a buzz saw into formal works of art. Beautifully executed, the sculptures look like wood or marble from a distance, but the monumental forms are built of paper. Although the finish of the pieces is smooth and polished like stone, the sculptures can be riffled like a book causing the printed texts and illustrations to magically appear. The construction is based on Chinese furniture joinery, the pieces fit together like the pieces of a puzzle, which can be dismantled and reassembled at will, and the books retain their original function and appearance. On a symbolic level, the nature of reading materials further informs the works with layers of meaning. Using recycled materials to make art addresses the voracious appetite of the consumer society that results in ecological problems of garbage disposal, the mindless destruction of forests, and the exhaustion of nonrenewable resources. So Chen salvages books like lost pets, prey to the de-acquisitioning of libraries in favor of cybernetic facsimiles, out of date textbooks, old phone books, and magazines. Such objects and the knowledge they contain have a totemistic power for Chen that derives from the traditional Chinese cult of literacy and its educational heritage. Living his youth in Taiwan, Chen inherited the Chinese love of literature, a reverence for history, and a belief in the sacrality of the written word. Like the Daoist dramaturges and their transformative performances, Chen transmutes the ephemera of the everyday world into something magical. His works point out the transience of human knowledge, and by doing so he asserts the spiritual world beyond the senses. In one series he recreated the heads of statues that were decapitated and brought home by Western collectors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This restoration series includes a variety of Buddha heads that represent the development of religious sculpture in China. Lately Chen has been crafting remarkably life-like portraits One astonishing work reduplicates Mount Rushmore, and the heads are placed around a miniature train installation, whose circuit travels through Egypt and Asia, represented by heads of antiquity. As the train travels its path, the voyage is geographical as well as temporal. Chen is also rendering portraits of Freud and ancient thinkers like Socrates, and even such contemporary figures as Barak Obama. For the show, Chen has provided a portrait of Mao and a portrait of an Old Testament prophet, both of who exerted enormous influence on their communities. Though they look monumental, his sculptures ironically convey a sense of fragility due to the paper material. Chen infuses his sculptural images with multiple associations, the most important of which is his love of literature and of books which he ruefully admits are no longer cherished objects but disposable and thrown away after but one reading. He considers the alarming problem of trash produced by the consumer society, and the evanescent quality of information, as the contents of books such as texts in medicine or the sciences that are constantly updated, the old texts are rendered irrelevant. Pang Yongjie, (www.gsr-gallery.com/en_artist.asp) has created an ephemeral world of harmonious congregations of people floating on overblown cumulus clouds. His large-scale painterly series, nearly monochromatic in its application of shades of white or light grey, deals with the struggle for existence: floating among clouds or at sea, his giant figures huddle together while a shark or predatory eagle circles threateningly. Some of these works are a response to the tragic earthquake in Sichuan, but the series predates the catastrophe by several years. In a prolonged interview Pang discussed the fact that he sees himself as a Confucian. Born near Confucius’ birthplace in Lu, Shandong, he grew up with the teachings that were conveyed to him as a child in a series of anecdotes to help form his ethical education. Social responsibility, humility, filial piety, and the importance of education were some of the lessons taught him in anecdotes about the sage. Thus, the earthquake was for him, and other artists like Ai Weiwei, a painful realization of the corruption of society, the unthinkable consequences of building schools with inferior materials. But sadly greed does not have a single habitation, it resides everywhere. Thus Peng’s images may be read as a plea for mutual respect and consideration for each other in a hostile world. The paintings display a vast landscape, sometimes a horizon in the far distance suggests an earthly terrain, other times an undefined ethereal zone is the setting. Floating in the murky sea of one such work is a large foreground view of a looming white figure. On its back are three chubby naked forms. Often it is not possible to identify the gender of these individuals. To the right are a much smaller pair swimming together and in the right foreground are sketchily drawn sailboats with dark hills looming behind them and in the far distance six boats filled with passengers float on the sea. In this abstract style the elimination of details results in a more generalized and more universal type of imagery. Pang stresses that since college he was painting in a very realistic manner, as are most artists trained in Chinese art programs, and that it took him a long time to work out a new style of painting, which he described as a breakthrough. The stark forms are not naturalistic; they are almost cartoon characters. Specifics as to gender or age are avoided, though in some cases the delineation of a figure’s hair suggests a bald male or coiffed female. So too occasionally rotund females have nipples articulated with pink pigment. Applied with broad brush and a palette knife, the pigment is richly textured, and the application suggests the kinetic movement of the artist’s process. Peng also has cast the cloud like creatures that float in his large-scale paintings into stainless steel sculptures, which ironically look like large round-bodied animals that walk on all four legs, but bear human characteristics. Though those in the show are single figures, sometimes smaller, child-like forms ride on the back of female figures, endowed with rotund bodies and breasts. Rather than interpret these creatures as critical of human behavior, they suggest our animal ancestry and the communal values once shared. Perhaps too one sees the cruelty of man, often metaphorically referred to as animalistic, as actually being peculiar to mankind. Zhang O’s (ozhang.com) early career focused on the issues of cultural and personal identity. In her series “Black Hair,” she photographed long Chinese tresses in a number of urban situations, suggesting her own transplantation from Beijing to London and the experience of immigrants everywhere. In one group she fashioned the tresses into calligraphic configurations on the damp nape of the model’s neck, making reference to both biology and culture. Later she considered her youthful years during the Cultural Revolution when her parents were transferred to a distant rural village in Wuhan. She returned to her hometown to photograph the children of the region where she grew up, stipulating that she wanted the children to experience her as a stranger, an outsider. So she refrained from speaking the native dialect. The pictures of Horizon from 2004 capture the look of the girls responding to the camera of an outsider; their expressions range from intrigued but slightly apprehensive, with guarded smiles, unblinking stares at the camera, or charmed by the attention. Zhang took the photos from three points of view: looking up, level and looking down on the subjects. In the final installation of the 27 photos, there are nine compositions of girls against a brilliant blue sky who squat looking down at the camera; these are mounted on the upper wall of the gallery. At center are nine girls who crouch and look directly at the camera; they sit in a green field of grass and in the lowermost row, the girls sit on their heels and look up at the viewer. The three rows of nine depict a vertical hierarchy culminating in a view of the sky, a reference to the Chinese concept of heaven, man, and earth. Viewing the work one encounters the young girls en masse and individually. This is a poignant subject for Zhang, for her these are the lost girls of China who, having survived premature abortion due to gender selection or adoption by westerners, still must struggle to survive rural poverty and ignorance in a male dominated society. It seems when Zhang left China and returned, she saw herself in the faces of these young girls. Similar themes are present in the project “Daddy and I” 2005-2007, a series of photographs of the girls adopted as babies by Americans and raised in America. The children vary in age, as do their fathers. The overwhelming impression is one of fulfillment on their faces, they have privileged lives and yet there are difficulties. The portraits, through setting, postures, dress, and expressions reveal the tender and complicated fabric of feelings of familial relations. The series also calls attention to the practice of selective abortion and the unseen consequences of a society increasingly comprised of males. These dual portraits convey the great happiness of father and daughter, but some faces have expressions of wariness and suspicion. In a more recent project presented in this exhibit, Zhang returned to China and photographed the youngsters in their hip teenage garb ostensibly posing for the camera at tourist sites. In The World is Yours (But Also Ours) she captures children gazing directly at the camera as if confronting the viewer to account for their behavior as caretakers of the future. Juxtaposed with such images of the new China as signs for the Beijing Olympics and wearing T-shirts that sport “Chinglish” expressions that teasingly suggest sensible phrases, these children are emblematic of the new generation of Chinese growing up in the global world of internet, western movies and TV shows, all of the superficial paraphernalia of daily life, lacking any grounding in Chinese culture and thought. Zhang’s work expresses her sensitivity to issues of modern life in China, she seems to want to warn us about the mistakes being made. Daoism, in its basic tenets and practices, affirms the importance of the female aspect. In its fundamental understanding of the dynamic dualism of yin and yang, the feminine principle is of equal importance. In this regard, Zhang’s work affirms the necessity of maintaining this balance in contemporary society. Li Qiang calls for a return to the rural life, he believes modern society has lost its connection to the earth and to the rural ethics that held China together for thousands of years. After graduation from college where he studied art, he returned home to his small village 3-4 hours outside of Nanjing where he lived for thirty years. Li only left his village a few years ago to live in Beijing and his works are still imbued with rural values. Li talks about the devastation of the rural villages, where life is naturally quite harsh, requiring long hours of labor to grow crops with the constant tyranny of weather, and the most recent devastation of the rural population caused by the emigration of its youth who escape to seek their fortune in the cities. Li himself had to leave for life was no longer sustainable for him there as an artist. Living in the city he has become increasingly aware of the pollution, corruption, waste and alienation of urban living, and the contrasts with the old community-oriented small town life that followed the agricultural calendar and the rhythms of nature. Like the Daoist paradigms of village life such as Peach Blossom Spring, there people, despite their hardships, lived close to nature and its cycles. Li Qiang’s work extols aspects of rural life. One set of works commemorates the noble earthworm, which by its movements through the soil, its droppings, and finally its shed carcass, made the soil fertile in pre modern China. He gathers the earthworms and immortalizes their traces first in plaster and then in bronze. Corn is also a major theme in his work. In one recent effort he commemorated the plant by making bronze life size sculptures of the tall stalks. In other works not only is the corn the subject of the composition, but he also utilized a technique of his own invention to make prints by impressing the corn itself into the ink with an old printing press that he rebuilt and adapted for this process. The work in the show from his series Seed employs this unique method of printmaking. First Li covers the husks with pigment, then, he impresses their form on the damp rice paper using his special retooled press. These portraits of ears of corn represent his earnest call to return to the old values of the countryside. Li points out that the corn has many uses, its rough husk, it silken skeins, its golden kernel and dried cobs are useful for housing construction, food for humans, and fodder for pigs. What is more the corn remains enrich the soil for the next crop. The beauty of this economy is real to Li. At the same time Li is painfully aware of the rigors of village life in rural China that have driven the youth to the cities where they fare as itinerant workers with few benefits of the old social welfare system—for them housing, education, and medical care are elusive. While in the villages, bereft of their youth, the old timers make their way, but are unable to keep the crop economy stable. Suffering from isolation and a lack of social programs in healthcare and education, they live a depressed, lonely and meager existence. Li’s works are a paean to the ancient agricultural values as eulogized by the great Daoist thinkers as well as a critique of the artificial and wasteful life in the city. Li Song is a painter of modern war pictures. In his realistic style, which is often monochromatic, his oversized oil paintings recreate modern war dramas. Like a still from a movie, he reenacts the drama of the moment. One painting set in Afghanistan shows the cold-hearted execution of soldiers. Another painting shows the attack of residents on a foreign immigrant, hatefully they hurl epithets and physically threaten the outsider who cowers at the center of a circle formed by the threatening mob. Li is quick to point out that this is not a recreation of a local event, but rather is based on actions from around the world. Li is extremely sensitive to such violent confrontations, whether between countries or communities. These paintings have won him great acclaim in China, not only because of their provocative anti-violence subject matter, but also because of the skillful manner in which the events are realistically represented, The narrative content is conveyed by the dramatic light, the posture of the figures in the midst of action, and the naturalistic details of the figures and their settings. The palette that renders one figure in brilliant color while the rest are painted in muted tones that are nearly monochromatic also heightens drama. Sometimes a female figure observes the action. Dressed in old-fashioned clothes she is a metaphor for the promise of China. Li’s humanistic concerns are also readily identifiable in his other works, which are prolific. The breadth of his subjects is great including large canvases with the sole image of a remnant of an animal bone, bare of its sinew and tendons, painted in excruciating detail; running horses made of glass, these horse are symbolic portrayals of China, which since antiquity saw the horse as representative of the strength and dignity of the country; and details of a building brick– the remains of old hutong; all are poignant memorials to the past. Most recently however he has begun a series of illustrations based on a phrase of the great third century bce Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi: “jin ji huo chuan” meaning the ladder to truth/heaven. It implies the difficulty of achieving excellence, the arduous and perilous climb to the top of the ladder. The first compositions comprise lighted or extinguished matchsticks arranged like a ladder on a blank red or dark grey background. From the match head swirls of smoke arise. More recent works discard the rectilinear structure for more freeform arrangement of the lighted matches. These works are spare compositions that in their limited color and calligraphic painterly style clearly allude to ancient monochrome Chinese ink painting. Here on the broad undifferentiated background the matches lay in a neat row, or in a casual heap. The repetition of the burning match creates an abstract composition of shape and color, and this strict rhythmic reiteration of the linear form is offset by their irregular patterns in which they are arranged and the curvilinear movement of the flickering flames and ephemeral smoke. In addition some of the series have traces of shadows projected on the canvas that seem to be caused by light shining through leafy trees. Liu Fenghua and his wife Liuyong (www.esteelie.com/en/artist_LiuFenghua.php ) make clay sculptures that replicate the most famous ancient artifacts– the soldiers of Qin Shihuangdi, the third century bce First Emperor. Using clay from the area around the excavation site in Xi’an, Liu Fenghua and his wife recreate the soldiers in both small and actual life-size figurines. By electing this subject they pay homage to the importance of the discovery and the fame that the site has achieved, for the clay soldiers are nearly synonymous with China to the hordes of tourists that visit the country. But historically the legacy of the First Emperor in China was that of a megalomaniac who brutalized his subjects, and as the great Han dynasty historian Sima Qian noted, he was not able to differentiate between the means to power and the means to retaining that power, so that despite his military valor and great skill, his reign shortly ended in ignominy. However the First Emperor was also responsible for implementing many pragmatic policies that enabled him to unify the diverse states of ancient China. These institutions had great longevity. For this reason revisionist historians of modern China have heralded him as a great man for his pragmatic approach to national unity. Thus the image of the clay soldiers is laden with a multitude of associations. In their artistic process Liu and his wife do not fire the clay sculptures, which would make them stronger, rather they allow them to dry naturally, which results in their remaining fragile. Their idea is to suggest the transience of people and materials with the specific intention that these works will in time decompose and return to the earth. In addition the soldiers are gaily decorated in a style of pop painting that draws upon the people, events and ideologies that had an impact on the Chinese people over thousands of years. These include philosophers like Laozi and Confucius; political leaders such as Mao, Lenin and Marx; scientists like Einstein; artists like Warhol, Miro, Mondrian and Picasso; writers James Joyce and Oscar Wilde; and movies stars like Elvis and Marilyn Monroe including several painted in Andy Warhol fashion; Bill Gates, maps of the constellations in the galaxy; and a number have insect themes such as lady bugs, or comic frog faces. Most frequent are images of Mao and symbols of the Cultural Revolution. Each soldier bears a single theme that is painted as a small motif in brilliant colors that covers the figurine like wallpaper. Both the pop style application of the motifs on the copies of these famous objects of antiquity and the delicate nature of the materials suggest that these people, ideological movements and such are also not long-lasting. Like several artists who have undergone the experience of the Cultural Revolution when history was rewritten and cultural institutions destroyed, Liu sees how history was manipulated for political purposes and maintains a sardonic and detached view of it. The very history of China, these sculptures suggest, is, like the images that coat the soldiers, decorative. In this way the artists affirm that the inner truth, the way or Dao is beyond such ideological constructs, which are just the frosting on the cake. Shen Jingdong, (www.chinasquareny.com/artists/…/ShenJingdong/…/frameset.html – ) is a veteran of the army in which he served as an artist doing stage settings for their musical and dramatic productions. It is perhaps for this reason, now that he has been discharged from the army, he has dedicated himself to painting images of soldiers. Usually it is one figure, shown in full or half body pose, with a dumb smile on his face. The technique is that of a caricature with no attempt to show any naturalistic effects. In fact Shen has evolved a convention for a simplified linear articulation of the face—eyebrows, eyes, nose and mouth; he treats the costume as a patch of color with simply drawn details; and applies the paint in an absolutely flat cartoon-like manner. Despite the apparent light-hearted appearance of the soldier, there is a deeper reading of the imagery. The brightly colored, empty-headed cartoon persona represents the role of the military in everyday life. This is not just a commentary on the Chinese military, but rather all military, a point of view made explicit in one work which shows the soldier with a long nose, which Shen says makes him a kind of Pinocchio, for the lies that are told to justify war. But it is also true that the army enjoys great respect in China and as a result exercises broad powers. Shen’s works show how the impact of military discipline deadens the soul, individuality and personal freedom. These soldiers then are the antithesis of the Daoist who extol freedom, an independent life lived in harmony with nature, like the men of the Peach Blossom Spring who dwell in the cove happily unknown to the authorities. However seemingly limited his theme, Shen’s execution is greatly varied, he makes single figure prints, large-scale paintings of single or multiple figures, shown half or full bodied. Moreover, he has created porcelain polychrome sculptures that recreate the image of the soldier in a number of formats—as a bust, half or full bodied figurine. Two of these sculptures are in the show. Here too, it is a generic figure with a bi-color palette, simplifying the image and by doing so imbuing it with symbolic meanings. These themes are also present in a series of paintings and sculptures that replicate the most famous painting in China, the one that portrays Mao’s first speech to the nation. Shen recreates the traditional composition in several media- large-scale triptych on canvas, and assemblies of porcelain and bronze figurines. In each recreation Shen interjects new figures into the narrative and in this way he demonstrates the politically motivated manipulation of history, for he is acknowledging the fact that over the last fifty years, every time the picture was repainted, there were many changes in the participants of the event–original members of the assembly who subsequently fell out of power were replaced with portraits of new men of influence. Since ancient times the path of politics was fraught with danger and intrigue, Daoists beseeched emperors to reduce the size of government and make it more transparent. Zhao Suigang, (www.zhaosuikang.com/) is an urban artist transported from Shanghai. Most of his work now comprises civic projects that are found throughout the US—colossal scale sculptures that include a skin of bronze letters that form a pair of up- stretched arms for a station of the Phoenix Light Rail in 2008. For the text, Zhao collected wise aphorisms of Native American traditions to harmonize the sculpture with its physical and cultural environment. For the Portland Oregon City Development Center, Zhao created a permanently lighted wall sculpture that covers the two stories of the lobby atrium and for which he collected contributions from local residents to create a text that he inscribed in their native languages with red ink on opaque illuminated glass blocks. For the Marriott Library in the University of Utah in 2009 Zhao made strips of thin steel act like ribbons of cloth to form 20 foot-arcs in the inner atrium of the Lobby. The strips, reaching several stories high, are made of a new material that reflects the colors of the rainbow when illuminated, thus as the ribbons of reflective steel entwine, they reflect the spectrum of light that enters from the atrium’s glass roof. Writing also covers these metal bands: multilayered inscriptions of text in Arabic, Hebrew, Chinese, and other languages. Zhao’s works consistently encompass a spiritual vision first expressed in his project Floating Poetry at the Djerassi Art Foundation in 1996 where Zhao inscribed Arabic and Chinese poems on death and love on irregularly-shaped colored pieces of resin that float in the creek on the property; the pieces flow up and down stream with the currents. This work embodies the Daoist principle of harmony with nature, as the rhythms of the natural elements animate the pieces of resin. Zhao affirmed the unity of spirit among the various religious traditions in pieces that appropriate passages from the holy scriptures of major sacred texts and then superimposed the verses by writing one over another on a translucent material that is illuminated from the rear. Treating the sacred texts as empowered messages, Zhao partakes of the Daoist tradition that reveres scriptures as the revelation of spirit with powers of its own. But these works which encompass his belief that all religions appeal to the same saintly spirit in man have been worked out in a number of surprising media– light and water sculptures, installations and even a computer program that offers up a series of events comprising animated excerpts of sacred scriptures of the world being written by an invisible hand accompanied by musical hymns of the same tradition, In the exhibit Zhou has crafted bas relief sculptures out of slender pieces of steel that are bent into script. The curvilinear forms decry the materials from which they are wrought. Painted brilliant polychrome colors, they can be read as the words, love, peace and man. Zhao takes rigid materials and makes them fluid, transforming the strength of steel into delicate calligraphy. He is the ultimate alchemist mutating materials into configurations that express his wonder of the universe. His organic forms embody the growth principle of the Dao. Dao Zi is a renowned art critic, author and professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Converted to Christianity during the Tiananmen incident, he has increasingly found solace in painting as a form of religious meditation. What is more, Dao Zi has revived the ancient technique of brush and ink on rice paper, which contemporary artists have by and large avoided. For thousands of years, Chinese artists have used the traditional materials of ink and brush on rice paper. The fluidity of the medium is determined by the amount of water mixed with the ink, a range that can encompass the darkest blacks to the most delicate washes. The rice paper easily absorbs the ink and no corrections are possible. Thus the artist needs to have a good idea of what he wants to accomplish before he lays his brush down, but he revels in accidents of nature and surprising effects. It is both controlled and spontaneous at the same time. The artist tries to achieve great variety in his lines, forming thick brush strokes, delicate tendrils of ink, short and long, straight and curvilinear lines. The artist must determine the amount of ink on the brush and its viscosity– whether thick or thin, whether laden with ink or not, and even a dry brush can achieve certain effects. The flying white technique, most admired in China, is accomplished with a brush loaded with ink, but so manipulated that white patches appear within the dense ink of the stroke, it is a kind of a miraculous performance. To a large extent, the quality of the ink and the amount on the brush determines the nature of the line. The artist strives to achieve versatility in his strokes– its thickness or thinness, its direction, its turning and overlapping of other lines. In large-scale presentations Dao Zi yields the brush with both great force and momentum and yet there are passages of incredible delicacy and poignancy. His grand complex abstractions are nearly monochromatic. Hidden in these monumental compositions the viewer can occasionally make out some spiritual imagery — an angel, fish, halo or cross. Thus Dao Zi has renewed the art of the traditional ink painting making modern large-scale works and imbuing it with a personal spiritual message. For Dao Zi making these works is a form of meditation. Like the great spirit mediums of Daoist practice, who in a trance-like state execute written messages from the spirit world, Dao Zi, in a nearly ecstatic state wields his brush. The awesome forms, so powerfully executed in Chinese ink on rice paper mimic the act of creativity of the universe. Hours of meditation result in numerous spontaneously generated images. The force of his brush expresses the vigor of his commitment. The viewer should imagine the artist standing upright and wielding his brush like a sword. Soaring movements yield large strokes speeding along the paper, while smaller gestures more slowly evolve. Harnessing his mental power, his energy flows to the tip of his brush. The scale is large, the movements grand, but delicate ink play can be appreciated under close scrutiny. Ciu Xiuwen (www.df2gallery.com/…cuixiuwen/cuixiuwen_gallery01.html) has been investigating the nature of cultural and personal identity within the confines of contemporary society. She began as a figurative painter, but soon turned to video and began to explore the new mores of Chinese society, Her video Ladies takes place in a public washroom in a Beijing nightclub in which she has secretly placed a cam recorder and filmed the various club girls fixing their hair, make-up, and clothes, or stashing the money they earned for personal services; one girl extorts money from a john; all of this takes place in the company of the humble bathroom attendant. In Toot Ciu made a mummy of herself, wrapping her body in toilet paper from head to toe. Then as the camera captures sprinkled water as the delicate tissue dissolves, she emerges, as if from a chrysalis, naked, in a statement of ultimate personal and artistic freedom. In the last decade Ciu has been working with an alter ego, beginning with a young schoolgirl dressed in her uniform. In Sanjie, the figures replace the characters in Leonardo’s Last Supperwith each figure of the girl posed in the posture of the actors of the drama. The effect is mesmerizing and raises many questions about this ultimate betrayal and the absence of women in the drama. As each figure is played by the schoolgirl, the question of the complexity of the character of man is posed– the same figure acts out the drama of savior and villain. Over the last decade the actor has grown up and new girls have worked with Cui on her series. Recently Cui’s model is around 15 years old and ostensibly pregnant. Sometimes it is a single figure composition in which the girl walks in the sea with the darkening sky rising behind her, or lies in the foreground of the Forbidden Palace in Beijing. By manipulation of the image in the computer, Cui creates a crowd of figures in front of Tiananmen Square. These situations suggest some of the difficulties of life in modern China and of the human condition in general. In the Exhibit’s Angel # 6, the girl appears in a number of postures on a mountain of sand within the walls of the Forbidden Palace. Here issues of the past and present, the role of woman in ancient society and their seclusion and inability to escape the confines of the palace suggests the greater metaphysical question of human survival and personal freedom inherent in Daoist wiritings. In Miao Xiaochun’s Fullness, one the works in the exhibition, Miao has used Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych the Garden of Delight, to create a series of stunning works employing a number of techniques. In the upper left section this C-print, hand-drawn cyborgs in various poses recall Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks. The black and white finely drawn sketches contrast with the rest of the work, which is brilliantly colored and therefore seems more voluptuous. Like Bosch’s work there are strange juxtapositions of the animal and human world, but the imagery for the most part draws on objects familiar in our consumer society. To the right there is a giant bagel from which legs and arms emerge, similarly figures exit a sliced orange, or legs come out of the top of two small pears. Some of the cyborgs drink soda from a large plastic bottle and from an enormous can. What is more, there appears to be a reference to Salvator Dali in the vignette of their resetting a large old-fashioned clock. Some of the figures have mechanisms instead of a head—one has a portable record player, another a clock. Interacting with each other, they chatter and gesticulate in a lively manner. A group in the foreground plays chess. This C print is but a section of a larger work called Microcosm that has in the mid-ground a procession of figures riding horses, donkeys, lions and other animals. A few figures haul a gigantic fish; they encircle a central grotto from which a figure rises holding a circle. Beyond there is a lake surrounded by groves of summer trees; two figures in a boat in the lake cast a net for fishing. Looming above in a cloudy grey sky is a large strange globular spaceship and in the left mid-ground is a fantastic Disneyland like architectural structure with spires and turrets. The complexity of the image is overwhelming, and the juxtaposition of the Eden like imagery with modern appurtenances, fantastic structures, and a spaceship elicits images of the past and future and the constant uncertainty of human existence. The many allusions to masters of western art like Leonardo and Dali, enforce the sense of time past. This phantasmagorical imagery, like the conjured visions of Daoist alchemists, combines aspects of our quotidian experience and of our dreams to suggest the complexity of human consciousness. In a tour de force of technology, the video version of the work is shown on three projectors focused on a single screen. These and other artists working today are acting on behalf of their fellow man, as healers, shamans, and advocates fulfilling the search for the Dao. 1 There are many translations of this text. This one, a compilation of a number of versions in English may be found at http://cuny.brooklyn.cuny.edu/caore9/phalsall/taote-ex.html 2 http://www.udel.edu/Philosophy/afox/zhuangzi.htm 3 http://www.udel.edu/Philosophy/afox/zhuangzi.htm

Fuel is Consumed, Flame Spreads Many people viewing Li Song’s latest painting series Fuel is Consumed, Flame Spreads(《薪尽火传》) admire his skill, imagination and passion. They are intrigued by the burning flame in his paintings, and study the significance of the image. The realistic technique evident in this series has its origins in Li Song’s first painting teacher, which was not a real person but nature! Fifty years ago, his family moved from the city to the remote countryside of northeast China. Life was simple and meager at that time—going from home to school was all that little Li Song did, but he watched the sky, mountains and the earth on the way. For some reason, Li loved the scenery between his home and school, he says it was the only thing that was not boring in his life and it inspired him to be an artist. As a diligent young “painter,” Li Song worked hard to paint everything in his daily life; he bound his works into books and secretly showed them to his classmates in the schoolroom until one day his teacher caught him. Usually the result of this kind of behavior was quite clear—the teacher would confiscate the books and directly throw them into the fire of the stove in the middle of the room. But this time he was asked to go to the office after class and unexpectedly, he got his books back with the teacher’s remark “good painting”! This was a magic moment in Li Song’s life—after that, though he never again brought his creations to the classroom, he felt the seed of “being an artist” burgeon in his heart. The forces that nourished the seedling include his first trip to Harbin that he made with his father. There they visited the studio where his uncle trained art students. As he explained, “His eyes, mouth and mind were opened: he saw plaster statues, watercolors, all kinds of art that he never saw before. He was so excited and could hear a voice in his heart clearly telling him “That’s exactly what you want to do”! Li Song made the decision to stay and study there. He began at zero—for his uncle put aside the works he was so proud of, and he had to begin again. He admits that while the other students looked at the model while painting, he watched his classmates’ every stroke and line. In the studio he realized that the importance of knowledge was equal to that of skill for a good artist, so he became a patient student absorbing cultural knowledge. He began to master the skill of sketching and watercolor, and only after that could he practice oil painting. Later he became a Chinese teacher in his mother’s primary school, but needing more freedom to be a professional artist, he soon left the job. The choice to be an artist is always difficult, but it was especially so in the 1980s when he was a member of Yuanmingyuan Artist Village. At the beginning, life was very hard—he lived in the yard and his neighbors were illegal vendors who sold fruit on the street. All that he owned was drawing paper, pens, a quilt and trishaw for moving. The artistic environment of the time included all forms of art—performance, kitsch art, etc. which confused Li who began to question his identity and artistic mission. Such questions tortured him and after being stumped for about 5 to 6 years he finally made the decision to go back to his initial point—when he was excited and moved. So he started his Portrait and Still Life series. For the still life, he chose the special subject of green onions of which his favorite writer Lu Xun wrote “there is cold green grasses under the snow”—just like the grasses, the green Chinese onion is resilient, after being buried under the cold snow for the whole winter, it can still break the earth and grow. So Li Song’s green Chinese onions are not only a plant but also the embodiment of energy, and the renewal of life. Such an appreciation of the principle of creation is no doubt related to Daoist theories of regeneration. Real artists never give up thinking, no matter if it is of their own life or social issues. Looking back on Li Song’s difficulty journey from his hometown to Harbin and then to Beijing, he continues to question himself, wondering “How big is the world?”, “Why did I leave home?” and now after 40, he finds there is no way back. His series Direction of the Bird transforms the feet of birds miraculously into piles of glasses—so the image conveys the pain of being broken with the realistic portrayal of brilliant, glittering and translucent glass. Li’s paintings convey a sense of the tragic, but at the same time they assure the power of renascence. In his Events series Li Song challenged himself to deal with historical topics, despite their being out of step with the art world’s current interests in photography, installation and video art. He raises serious questions about war and racial hostility but does it in an ironic tone, using drama and ridicule, like the Daoist poets, to encourage people to confront these questions for themselves. Though Li Song is always against “returning to the ancients” in a dependent way, for he asserts we live in this moment, yet he believes we must draw on the experience of the ancients, the valuable treasure of wisdom passed down by our ancestors, and keep it fresh. We need spiritual awareness in this fancy and materialistic era. Sometimes Li Song misses the romantic 80s’ when artists would gather together just to discuss their dreams, love life, and classical literature; when they could recite entire monologues from the movies; and sing, shout, and even cry together. “Getting warm with the fire from heart” is the way Li Song describes that period of time. But the spiritual fire is not extinguished and this is evident in the piece on display in the exhibit, “Jin ji huo chuan: Ladder to Heaven. Though matches are a common thing in everyday life Li Song has ennobled them, making them large in size, emitting brilliant flames, and uses them to create ladders or a bridge, a piano or a violin. He stresses in his technique a linear element that is related to Chinese calligraphy, which is the medium used to relate spiritual truths. Against the dark background of this series, we can witness the matches as individual lives—each jumping and shining. By extension they also represent Li’s journey which he sees in terms of the great Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou‘s idea “As the fuel is consumed, the flame spreads” as a celebration of his on-going struggle and of nature’s perpetual transformation.

|