Nature, Once Removed

Introductory essay by Sean McCarthy

In his 1977 essay “Why Look at Animals?” John Berger explores the idea that, through the mechanisms of late capitalism, humankind is completing a process “by which every tradition which has previously mediated between man and nature [has been] broken.” He traces the relationship between humanity and nature from prehistory — in which animals “were with man at the centre of his world,” entering the imagination and providing the first metaphor and the first subject matter for painting — to our contemporary reality, in which the observation of real animals is largely relegated to zoos or mediated by television. In this world, the “animals of the mind,” those of “sayings, dreams, stories, superstitions [and] language itself,” have been transformed into children’s playthings and cartoons.1

This process had an indelible effect on the childhoods of artists of my generation, born in the years surrounding the publication of Berger’s essay. For many of us, the imaginary landscapes around which Wile E. Coyote chased the Road Runner were as vivid in their own way as any experienced firsthand. Menageries of stuffed animals, many of them based on characters from cartoon franchises, became the objects of projected feelings and fantasies. The stuff of the earth, its landscapes and all its inhabitants, was primarily confronted in the form in which it appeared in advertising, acting as signs of anxiety and desire. Those of us drawn to nature as a subject for our art have found that our sensibilities were permanently altered by this secondhand experience of the natural world.

Meanwhile, following Pop in the 1960s and postmodern appropriation in the 1980s, it seemed that nature as a subject for pictorial art was largely moribund. The use of catchphrases such as “forest of signs” to describe the contemporary condition was an indication that culture had replaced nature as the model and font of artistic creation. However, during this time a small handful of artists — often marginalized by the critical apparatus of the art world — found ways to incorporate subjects from nature into works of art that contextualized them within an impurely Pop or post-Pop sensibility. Their work has provided important precedents for that of their younger peers, in which a remarkable resurgence of interest in animals, plants, and landscapes as subjects can be seen, and this exhibition attempts to trace that thread by including work by both seminal and emerging artists.

Melissa Barrett’s recent collages depict public aquarium exhibits and the children who visit them. Contra Berger’s vision of zoos and the like as depressing, inevitably disappointing sites of extreme marginalization, Barrett lovingly evokes the sense of wonder children often feel in the presence of the otherwordly beauty of sea life. She does not deny the artificiality of the aquarium as a structure, where the glass that separates us from the creatures in the water is as much part of a frame as that which separates us from the lively surfaces of Barrett’s collages; rather, these pictures are themselves clever meditations on the artifice of pictorial art. The cubists introduced collage into painting as part of their assault on perspectival space and other illusionistic devices of Western painting, and Barrett inverts that operation by enlisting buttons, beads and bits of fabric and lace in the service of illusionism, rendering these representations of the aquarium’s highly artificial exhibits of sea life with a remarkably convincing sense of light and space.

Melissa Brown’s Image From the Earth’s Iron Core uses collage to very different, if no less complex, ends. The image itself has no truck with naturalism or illusionism; according to Brown, it is a spiritual diagram of energy emanating from the Earth’s core appropriated from a book on the Gaia principle. Brown’s interest in the image stems from the familiar geometric forms that make it up. The ubiquity of such forms dovetails in Brown’s practice with the ubiquity of lottery tickets as vernacular printmaking — that is, in spite of the often extraordinarily high quality of their printing, lottery tickets are bought and discarded in such spectacular numbers that they literally become part of our urban landscape. Likewise, the mystical aspect of the image corresponds with Brown’s conception of the mysticism of playing the lottery, an act in which a possibly willful misunderstanding of scientific or mathematical principles — in particular, those of probability — links up with strong feelings of hope or desperation to create the illusion that one could beat the forces of the universe at their own game.

William Crump’s Grandfather Mountain Revisited is an unusually reductive piece for the artist, made up of a naturalistically rendered graphite drawing of a beard in profile superimposed over a series of flatly painted, brightly colored bands of gouache. In spite of its apparent simplicity, the drawing is full of interesting ambiguities and contradictions. The contiguous bands of color recall those that show up in certain late, high-modernist abstractions by Louis or Noland, but here are gently forced into contours that evoke stratifications in a cutaway view of a mountain. Likewise, in spite of its relatively clear status as a representation, the drawing of the beard is so decontextualized that an unequivocal reading is nearly impossible; first impressions may run through fire, smoke, clouds, or rain, depicted with varying degrees of stylization. The ambiguities of the image as a whole would seem to be resolved humorously by the title, but its combination of genealogy and geology is itself apparently nonsensical unless one is aware of the eponymous mountain’s existence in Crump’s home state of North Carolina.

Lorenzo De Los Angeles’s Kaleidoscope, while containing its own complexities, touches on a number of themes explored in the pieces discussed above. For instance, like Grandfather Mountain Revisited, it combines seemingly contradictory modes of representation, albeit within a more uniform facture. In this case, diagrammatic and trompe-l’oeil information is superimposed upon a perspectival space in which starfish in a tank look through a kaleidoscope. The radially symmetrical patterns they see (which recall the composition of Image From the Earth’s Iron Core) appear as diagrams surrounded by dotted lines and scissors. This conceit, along with the drawn intimations of cracking glass parallel to the picture plane, also recalls Barrett’s play of artifice and illusionism — the diagrams, with the attendant instructions for cutting them out of the drawing, remind us that we are looking at a flat sheet of paper, while the images of cracked glass suggest an illusion that the glass of the frame is breaking, undercut by the same kind of mark-making elsewhere indicating an entirely different kind of illusion of space; and, of course, we are once again reminded of the parallel experiences of viewing animals and drawings behind glass. Meanwhile, the image as a whole raises a number of questions, the foremost being, how do the starfish interpret the images they see through the kaleidoscope? Does the radial symmetry of the patterns suggest that they interpret them as images of their own bodies? Or are they seeing something more celestial, or more mystical? And, given that the kaleidoscope is a human-made object, and therefore the patterns — although arrived at to some degree by chance — are the result of human creation, we might be led to an inverse question: what sort of ways have human beings projected meaning onto natural phenomena, and how truthful or useful have those projections been?

Nicholas Di Genova’s Upright Shepard Walker offers an answer to a different question: what kind of creatures will roam the earth after human beings have managed to eradicate themselves? In this case, Di Genova proposes something like a very fierce-looking dog-penguin hybrid. Di Genova, like a number of artists in this exhibition, spent his childhood developing an artistic sensibility much more informed by cartooning than by the fine-art tradition of painting. In particular, Upright Shepard Walker bears the influence of Japanese mecha anime in the way hair and flesh have been drawn to look peculiarly robotic, as well as the use of the technique — adapted from cel animation — of drawing and painting on layered transparencies to achieve depth. It is also significant that Di Genova came of age as a street artist, wheatpasting his illustrations onto buildings in his native Toronto. While the formal range of contemporary street art is far too broad to characterize generally, common traits include strong graphic contours and mannered stylizations similar to those in Di Genova’s drawings.

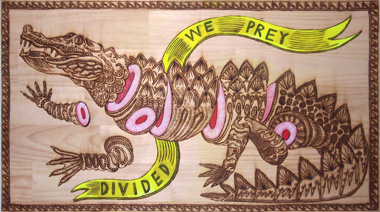

Felix Esquivel’s drawing Divided We Prey, made with a woodburning tool and acrylic paint, depicts a rampant crocodile cut into pieces with a banner running behind announcing the title. The image is a direct reference to a political cartoon by Ben Franklin that features a snake divided into sections — each representing one of the eight colonial governments of 1754 — and captioned “Join, or Die.” Franklin was exhorting the colonies to unite with a motif based on the folk belief that a snake that had been cut into two would return to life if its halves were joined before daybreak. Esquivel’s drawing, made in 2007, re-imagines Franklin’s print as an exemplary Bush-era political cartoon. First, Esquivel has chosen a crocodile rather than a snake to represent America; this is significant because the only state in the union in which the crocodile is indigenous is Florida, which was, of course, the site of the infamous recount that put Bush into office in 2000. Also, unlike Franklin’s snake, it should be noted that Esquivel’s crocodile is not dead as the result of its having been cut apart, but rather undead. As artist Zak Smith notes in his recent memoir, zombies were — appropriately — the most popular monsters of the Bush era, since “they are unusual, among monsters, for being inferior to their victims and winning only by weight of numbers, and for having no brains, but wanting to eat them.”2 Esquivel’s crocodile is a sad, funny emblem of the United States under the leadership of George W. Bush: divided by a poisonously partisan political atmosphere, wounded and angry, fiercely blundering into two protracted, costly wars.

Chie Fueki’s Mt. Fuji is a history picture of a different sort, a contemporary take on one of the most well known and frequently portrayed subjects of the golden age of Japanese printmaking. Mt. Fuji is imagined here as hot pink, oozing into the bottom of a strange geometric space and spewing forth flowers, an obliquely angled disc and a half-hidden skull. One may be forgiven for being unaware of the fact that Fuji is an active volcano; its last eruption took place in the early eighteenth century, and in its most famous depiction — Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa — it is a placid icon in the background of an otherwise startlingly dramatic scene. That print, of course, is part of a tradition that, along with photography, is often credited as a catalyst in the disruption of the Western tradition of linear perspective that led to modernism in painting by providing a model for the flattening of pictorial space. It is no coincidence that Fueki situates her Fuji in a flattened cube of the sort familiar to us from graphic works of the late 1960s and early 1970s by artists like Albers or Judd. By doing so, she collapses roughly one hundred years of modern art history into one image. Moreover, if we acknowledge the role Japanese prints had in the “death” of perspectival space in Western art, then we may have a clue as to why Fuji’s eruption in Fueki’s image is characterized by a memento mori partially obscured by ornament and geometry.

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s Turmin Fluff is a portrait of one of the many creatures that occupy his mythopoeic universe, in this case a mound. Mounds, according to Hancock’s formulation, are human-plant hybrids rooted to the earth by their skeletons; they survive by absorbing nutrients from rainwater as well as from insects that they trap with their sticky, black-and-white skin. Hancock explains the existence of mounds with a myth involving a family of prehistoric ape-men, the patriarch of which, Homerbuctas, creates the mounds by masturbating onto flowers in a garden. His wife, Almacroyn, discovers the mounds and reveals their existence to their children, Brouthescam and Cromalyna, who subsequently attack their half-siblings in a fit of jealous rage. As a result, the two ape-children are swallowed by the earth and banished to an underground realm, within which they become the progenitors of a cruel, ascetic race known as vegans. Of course, vegans in contemporary America are people who eat only plant matter and exclude the use of animals and animal products in their diet and lifestyle for moral, ethical or spiritual reasons. To a mound, however, this code would certainly have sinister implications, and, indeed, vegans are the villains of Hancock’s story. This use of mythopoesis to invert a familiar moral paradigm echoes the work of Blake, although a number of more recent influences — Henry Darger’s In the Realms of the Unreal, or Chris Claremont’s work on X-Men, for instance — are equally relevant. Turmin Fluff, for its part, is a sweet portrait of a peaceable grotesque in a garden, as yet unfamiliar with morality or mortality.

Arturo Herrera’s Mine, at first glance, resembles Pollock’s paintings of 1947–50 in its stringy, multilayered, all-over abstract composition. One should remember that Pollock, when asked by Hans Hoffman in 1942 if he worked from nature, replied, “I am nature.”3 Pollock at the time was in his second year of Jungian analysis, and his response may well have been influenced by Jung’s conception of the collective unconscious as a unifying force underlying all of reality, an idea that drew upon alchemy, Eastern philosophy and contemporary developments in physics as well as Jung’s training in psychology. Whereas Pollock’s images are formed by a collaboration between unconscious gestures and the force of gravity, Herrera arrives at similar formal ends through an entirely different process of appropriation, abstraction and collage, through which he explores the hidden lives of ubiquitous popular images. Here, although much of the representation has been obliterated, the telltale tapering and swelling of lines in the mostly white, cut-paper layer of Mine reveal their sources as Disney cartoons. These lines flow over a black ground that is itself covered in delicately drawn blue lines that alternately suggest hands, vines, leaves and rippling water. By reconciling “kitsch” imagery much abhorred by most of the Abstract Expressionists and their critical supporters with a formal language borrowed from one of their foremost practitioners, Herrera ends up affirming the evocative power of abstraction in a media-saturated culture.

Jackie Hoving’s Common Buzzard depicts a scene that most of us who live in contemporary urban America rarely if ever observe firsthand — that of a carnivorous animal in mid-kill. If anything, we are likely to see it on television, perhaps narrated by Sir David Attenborough. Berger comments on this kind of secondhand experience as being the result of a “technical clairvoyance” which humans have achieved by embedding high-speed cameras with telescopic lenses in the dwelling places of wild animals.4 Hoving reinforces this sense of remove in the way she develops the image out of cut-and-pasted papers that have been printed or marbleized to varying effect. That is, while she maintains the observed contours of the animals depicted, the information inside those contours is frequently decorative, obscuring the naturalism of the image with overt artificiality. Her use of a floral pattern in the image of the buzzard is of particular interest, since the pattern’s motif is itself a stylized image of a natural form, in this case one associated with life and beauty. To imbed it within this representation of a creature in the midst of a violent act underscores the way romanticized ideas of nature (which frequently arise out of a condition of separation from nature and its processes) frequently underplay or altogether ignore the pervasive violence of the natural world.

Elizabeth Huey’s Train Stop features haunting examples of what Berger refers to as the “animals of the mind.” In fact, one of the figures (the stag in the coat and short pants holding the swaddled baby bird) is appropriated from Grandville’s Public and Private Life of Animals, which plays an important role in Berger’s text. He writes that the animals in the series “have become prisoners of a human/social situation into which they have been press-ganged.”5 This takes on rich connotations in the context of Huey’s work, which for the last several years has been a meditation on the history of mental illness and its treatment. Although animals appear relatively infrequently in her work, the fairy-tale quality of the figures in Train Stop is entirely of a piece with Huey’s storybook asylums and the mysterious woods in which they are often situated. The relationships between the anthropomorphized animals in the piece recall the alienated qualities of Kokoschka’s figures: although they occupy the same physical space, they seem disconnected psychologically and emotionally. Spatial and narrative elisions trouble any attempt at a definitive reading of the drawing’s meaning. The brushwork that makes up the largely abstract ground is more suggestive than descriptive, and the stag might be about to depart with the baby or to set it on the tracks, while the she-wolf’s pose might alternately indicate fretting, praying or begging. What might have been elements of a children’s story are presented in a disturbingly ambiguous arrangement.

This last sentence might also be used to describe Daniel Johnston’s untitled drawing from 1998. The reception of Johnston’s work has long been haunted by his very public battles with mental illness, which were subject to a harrowing — if loving — examination in Jeff Feuerzeig’s 2005 feature documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston. Johnston is better known as a singer-songwriter than as a visual artist, although in his case, these two means of expression lead to remarkably similar ends. Johnston’s songs are characterized by disturbing bittersweet lyrics sung in an uncannily childlike voice, and these qualities take visual form in a drawing like Untitled, whose cartoon ducks and slug-like creature are drawn with a kind of naïve, vicariously enjoyable abandon but whose expressions and arrangement on the page begin to take on an unsettling quality. There is something manic about the round, staring eyes and nervous grins of the ducks, and the largest one — the orange one on the left — looks particularly troubled, with his uncomfortable grimace, the inexplicable torsion in his neck, and the insistent marks used to outline his left eye. The ducks also seem to be walking in no particular direction while arranged in an irrational, contradictory space indicated by inconsistently cast shadows. Only two are given a sense of purpose: one by virtue of the Bible in his hand, the other by his gesture of presentation in the direction of the slug-like creature; otherwise, we are presented with beings moving seemingly purposelessly through an existential void, no less so than if we were looking at Giacometti’s City Square of 1948.

Darina Karpov’s Lucid Accumulations brings to mind Bataille’s final words in his definition of informe, or the formless: “…affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is like a spider or spit.”6 From a distance, Karpov’s drawing seems to dispense with every compositional rule one could think to apply to a work of pictorial art; the image it presents appears to be a ropy, asymmetrical network of spit floating in an inky vacuum. Upon close inspection, this fluid indeed contains a universe, or at least a world, of finely articulated plants and animals fighting their way out of the ectoplasmic slime. Pieces of this world open into new, tiny spaces, such as the one in which a tree seems to grow obliquely into or out of a bear’s body. There is something seemingly hopeless about this process of materializing and growing, since the available options seem to be to reincorporation into the gunk or breaking free into cold, empty space. Perhaps, though, as suggested by the title, this image is a kind of allegory of thinking, and the appearance or disappearance of these organisms is to be no more celebrated or mourned than those of thoughts passing through our minds.

Gary Panter’s Nose to Nose features a dense, gestural abstract ground over which he has drawn a scene of bizarrely funny anecdotal detail that suggests a section of Bruegel’s Netherlandish Proverbs as interpreted by Tex Avery. Like most of the paintings he has made throughout his career, Nose to Nose takes a landscape format, and, in spite of the layers of appropriation, mediation and stylization to which his images are typically subject, a fundamentally natural, biological conception underlies Panter’s painting process. As he told Robert Storr in 2007, “When I start painting I think of where’s the water. You don’t necessarily see the water, but that’s the first thing I think about. You already have air, or you’d be dead. You have a while to find water.”7 Panter has also spoken evocatively about the handful of years he spent as a child in Brownsville, Texas, where “it was very colorful. There used to be orange and lemon groves that had big cutouts of cartoon characters, like a big Porky Pig head, ten or fifteen feet tall, on the side of the road by these fruit stands…”8 It was during this time that his father managed a dime store, where Panter was introduced to cheaply produced Mexican comic books with off-register printing, which provided an important precedent for the some of the formal devices he would develop in his mature work. His ability to synthesize formative experiences like these with an open, encyclopedic enthusiasm for art objects of both exalted and vernacular status makes Panter a critical link between artists like Wesley and Saul, who emerged during the Pop era, and the younger artists in this exhibition.

Chris Patch’s two drawings (both untitled) are, perhaps, the most deceptively simple pieces in the show. Both depict a similar, if not identical, scene in Maine, and both are watercolors of landscapes, a combination of medium and genre that one often associates with Sunday painting and dilettantism. Yet it would be a tragic mistake to read these paintings that way. Patch, a scholar of marginalized forms and genres with a particular interest in folk art, botanical and natural history illustration, and other forms that exist on the periphery of “high” art, nevertheless borrows significantly from high modernism in these pieces. Their serial nature, and their shift in temperature, recalls Monet’s paintings of haystacks or of the Rouen cathedral at various times of day; the specific quality of Patch’s mark-making, particularly in the lower third of each drawing, recalls the controlled gestures of Jasper Johns. In this way, Patch’s watercolors suggest a connection to the paintings of his former teacher Jim Nutt, in that they similarly use what are, by the high-concept, spectacle-driven standards of the contemporary art world, modest forms and formats (in Nutt’s case, intimately scaled portraits of imaginary women) that are nevertheless profoundly historically and pictorially literate and ambitious in their reconciliation of a range of high and low cultural traditions.

Lamar Peterson’s Untitled (The Doe) features a reindeer and a pine tree in a flat, manicured landscape. Two small clouds float overhead, while a segment of white picket fence (the very emblem of middle-class suburban prosperity) occupies the foreground. Together, these elements suggest an image of a skull, indicating that all is not well in this seemingly placid scene. This kind of subliminal device is familiar from Dalí’s paintings of the 1940s, in which figures and elements of the landscape regularly merged to form some playful or sinister visage. Here, the two figures in the center are icons of Christmas celebrations—the evergreen tree, a vestige of pagan solstice ceremonies in which it functioned as a symbol of fertility and bounty, and the reindeer, a member of a species of the remote far north. In Peterson’s drawing, both have been displaced from their original contexts, much as they have been within the Christian tradition they have come to emblematize; furthermore, these natural forms are subject to heightened alienation as a result of being co-opted by celebrants of this now largely consumerist holiday. Peterson plays up this uncomfortable subtext by situating these images associated with winter in a bright, green landscape, perhaps a nod to the potentially lethal effects of global warming, reinforced with an archetypal image of death.

Angela Piehl’s work also traffics in the sometimes-sinister undertones of bourgeois lifestyles, although its dark, black-and-white atmosphere is a world away from Peterson’s ironically bright, cheery palette. Part of Piehl’s process involves culling editorial and advertising images from magazines like Martha Stewart Living, which she then atomizes, abstracts and combines with images of organic material like flesh, bone and muscle to create semi-narrative biomorphic abstractions. Crowning, for instance, suggests a fat, wormlike creature made up of pearls, fabrics, antlers, flower petals and tentacles (among other things), pushing its way down and through a space surrounded by waves of curling hair. It is significant for Piehl that somewhere in the DNA of this creature lay imagery that once had a life in media made for women, coded with standards and imperatives regarding femininity in contemporary American culture. The piece’s title, with its alternate suggestions of bestowing, surmounting, climaxing and birthing, offers some evocative interpretative clues, but the work as a whole remains cryptic, perhaps as an antidote to the implicit essentialism of its original source material.

Peter Saul’s Untitled (Study for “The Neptunes”) is unique in this exhibition by virtue of being a working drawing, in this case a study for one of his recent large acrylic and oil paintings. Saul, like Wesley, came of age in the Pop era but soon ran afoul of its codifying dictates. His early work, with its vestigial abstract expressionist tendencies, was thought to be too painterly to qualify as “true” Pop, whose facture, it was felt, should more closely imitate the relative seamlessness of mass production. Saul subsequently made a virtue of doing everything wrong, inverting every principle of reason and good taste prescribed by the art world elite. Throughout his career, he has regularly enlisted animals as agents in this campaign, for instance by painting an army of ducks invading the space of Jasper Johns’ Map, or imagining a tiny dog chomping down on the left hand of Jesus in his Last Judgment. Here, Saul imagines the Roman god Neptune and his sea creature minions as a family unit similar to those in early Hanna Barbera cartoons, like The Flintstones. Although relatively innocuous as compared to most of Saul’s output — which typically plays fast and loose with art-historical tropes and hot-button political and social issues in narratives populated by day-glo grotesques — there is nevertheless a characteristic moment of cartoon violence as the giant octopus on the left blithely sinks a ship.

Craig Taylor’s drawings, both enigmatically entitled Lucifer, are perhaps the most painterly drawings in the exhibition. The first is an image of what appears to be a cartoon rabbit or bear in the process of losing its structural integrity, as the marks used to indicate its face are beginning to float away while the lower part of its body is being enveloped in a disheveled grid. The second resembles a landscape whose marks coalesce into highly ambiguous images that seem to suggest both city buildings and plant life against a silvery blue sky. The drawings’ ambiguity, their humor and anxiety, and their evidence of process and suggestion of transformation are typical of Taylor, who for the last decade has maintained a practice of omnivorous abstraction, drawing from an enormous range of precedents and sources to make work of highly aestheticized grotesquerie. His drawings, paintings and sculptures embody Bakhtin’s formulation that “grotesque images with their relation to changing time and their ambivalence become the means for the artistic and ideological expression of a mighty awareness of history and of historic change. … The new historic sense that penetrates these images gives them a new meaning but keeps intact their traditional contents: copulation, pregnancy, birth, growth, old age, disintegration, dismemberment. … They are contrary to the classic images of the finished man, cleansed, as it were, of all the scoriae of birth and development.”9

Christopher Ulivo’s Go Pinatubo, Go! is an ink wash drawing of the Filipino volcano which most recently (and disastrously) erupted in the early 1990s. Its dramatic eruption is framed on either side by a monstrous animal: on the left, a turtle-like creature who resembles Gamera, the classic kaiju movie monster; and on the right, a giant screaming eagle. Together, this imagery suggests a number of associations, for instance the WWII battle over the Philippines (with the creatures embodying Japan and the U.S.), an East-meets-West theme reinforced by the use of Sumi ink in the service of American-style cartooning. For our purposes, it is especially relevant that the drawing pairs an image of a natural disaster (in this case, a volcanic eruption) with those of creatures that evoke golden-age, man-in-a-rubber-suit cinematic behemoths. When we watch a film like Godzilla or King Kong, we tend to think of the monsters as horrifying natural disasters themselves — they come from the sea or the jungle, etc., to wreak havoc on humankind — but we also see them as the protagonists of their films, and are inclined to sympathize with them and to take vicarious delight in the destruction they cause. The same dichotomy arises when real natural disasters, as portrayed on television, are transformed into spectacle. The screen provides an illusory access to the genuine human misery that such an event causes, while inevitably aestheticizing its destructive power. By pairing these two kinds of calamitous spectacle together in one drawing—which is itself enjoyable, with its funny characterizations and casually vigorous gestures, and whose very title cheers on the devastation—Ulivo problematizes the pleasure we take in our roles as spectators.

John Wesley’s untitled drawing presents a comical scene of revenge, in which an exasperated pink fish and a startled seabird play out a reversal of their usual predator-prey relationship. As with most of Wesley’s work, it splits the difference between funny ha-ha and funny peculiar, provoking wry laughter as it raises a number of questions: Why is the fish so pink and scaleless? Why doesn’t it have gills? Why does it have the eye of an old man? Why are the figures floating the way they are, superimposed onto the horizon? Which way is the gull’s head turned? What exactly is that tan cloud? Is it an indication of the fish’s frustration, or maybe an empty thought bubble? If it’s just a cloud, why is it tan? Everything about the image seems so carefully designed and executed that these peculiarities must exist for some reason, however opaque. This confounding quality is an indication that we are looking at art rather than a simple cartoon, and it extends to the disarmingly simple formal means Wesley employs: although the flat fields of color and black outlines evoke the language of cartooning, a more fruitful comparison might be made to Attic vase painting, given Wesley’s masterful arrangement of positive and negative shapes and the playfully mythic qualities of the image. Wesley’s work can be thought of as a kind of urbane, stylish counterpart to Peter Saul’s hysterical cartoon expressionism, and it has been a no less profound influence on the sensibilities of many of the other artists in this show. As Dave Hickey put it in his 2000 Artforum article “Touché Boucher,” “at the moment of Pop’s inception, American art was starving in the midst of plenty, and…young artists like John Wesley, who began exhibiting in the early 60s, could hardly have failed to notice that, while modernist painting was obsessively refining itself out of existence, the full resources of historical art making, all of its traditional idioms and repertoire of emblematic imagery, lay immediately to hand, alive and available in the pastures of vernacular culture.”10

1. John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?” in About Looking (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), pp. 3–28.

2. Zak Smith, We Did Porn (New York: Tin House Books, 2009), p. 57.

3. Dorothy Seckler. “Oral history interview with Lee Krasner, 1964 Nov. 2–1968 Apr. 11,” Smithsonian Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/krasne64.htm

4. Berger, About Looking, p. 16.

5. Ibid., p. 19.

6. Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997), p. 5.

7. Tom Spurgeon, “A Short Interview with Gary Panter,” The Comics Reporter, http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/resources/interviews/14541/

8. Gary Panter et al., “Biography” in Gary Panter, ed. Dan Nadel (Brooklyn: PictureBox, 2008), p. 286.

9. Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), p. 25.

10. Dave Hickey, “Touché Boucher: John Wesley’s Gallant Subjects,” in Artforum, October 2000, pp. 116–121.