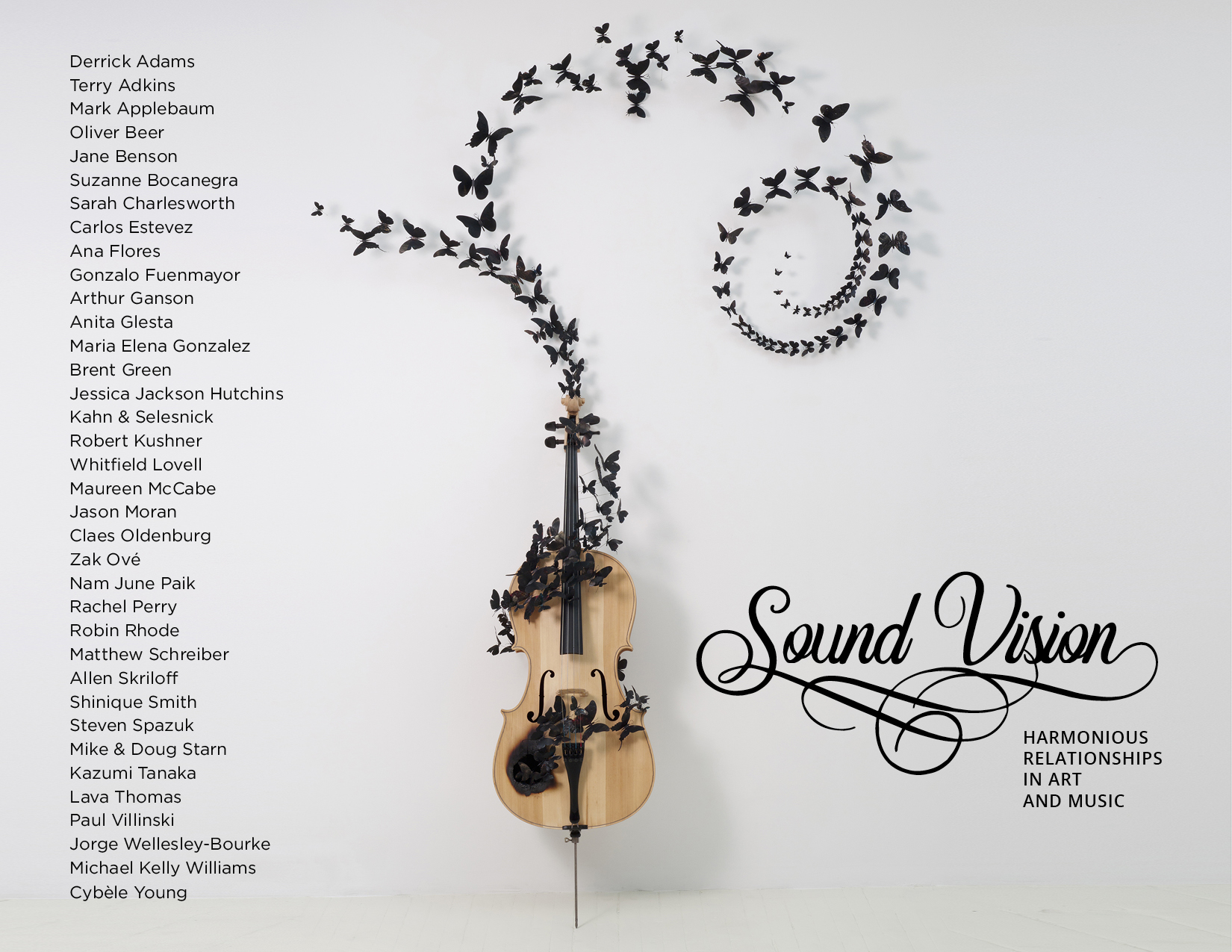

SOUND VISION

Harmonious Relationships in Art and Music

Co-curated by Independent Curator, Alva Greenberg and Lehman College Art Gallery Executive Director, Bartholomew F. Bland, Sound Vision: Harmonious Relationships in Art and Music, appears virtually from January 23, 2021 to June 30, 2021. Featuring three dozen contemporary artists and more than 60 works of art that reference—either literally or conceptually—music and sound. The project continues Lehman College Art Gallery’s long-term commitment to group thematic exhibitions combining well-known artists and established mid-career artists with emerging regional talent.

Many artists attempt to transform the intangible and ineffable qualities of sound into physical form, allowing viewers to see music in art. Just as the human senses of seeing and hearing have always been interrelated, visual art and music have long been complementary– the presence of one is capable of heightening perceptions of the other. Today, music is a constant–sometimes happy, sometimes relentless–companion to our daily lives. There is no escaping it. In elevators, waiting rooms, restaurants, and through ear buds, our lives are lived with a sound track as background accompaniment, in a world where silence can breed anxiety. In their own experience of sound, visual artists are inspired to use the auditory language of music as “source material” for the creation and translation into their visual work.

The symbols and allegories of music and the sounds – both vocal and instrumental – are referenced in the great historical and mythological themes of such historical figures as Michelangelo Caravaggio’s Lute Player (1595), Gaspare Traversi’s The Music Lesson (1760), William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress (1733), Nicholas Poussin’s A Dance to the Music of Time (1634), William Harnett’s The Old Violin (1886), Henri Matisse’s The Piano Lesson (1916), and Joseh Beuy’s Homogenous Infiltration for Grand Piano (1966). Artists such as early 20th-century Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, strove to express the spirit of Kandinsky, strove to express the spirit of music through color, line, and abstract forms. The contemporary artists selected for this exhibition have embraced the challenge of making music the core of their creative process by turning the music into some form of visual manifestation. Their approach can be as direct as an artist transposing a specific piece of music into an artwork or an instrument into a sculpture, or as opaque as using a natural phenomenon—the human heartbeat—to create a fascinating rhythm.

Thoughts on the Relationship Between Art and Music

Alva Greenberg, Guest Co-curator

Art and Music have long held hands. The 21st century has seen an increase in the blurred division among artistic categories, leading to a growing crossover of genres. Actors turned directors turned writers turned visual artists proliferate in the creative fields. Today, artists and performers can flourish in multiple categories at any one time. Take, for example David Byrne: we primarily think of him as a musician, but he attended both the Rhode Island School of Design and the Maryland Institute of Art, is listed on the artist roster of Pace Gallery in New York and opened a musical, American Utopia, on Broadway in 2019.

While making the shift from musician into visual artist appears to happen fairly frequently, it is much harder to find the reverse. Painter Romare Bearden stands out as a major artist of the Harlem Renaissance who also actually composed music, unlike sculptor Harry Bertoia who played scoreless concerts on his Sonambient sculptures.

The strong connection between art and music runs on many parallels, and the language of visual art mimics that of music. In both, we talk about color and tone and gesture. We discuss the lyrical qualities and harmony or discord of a painting or sculpture.

Sound Vision: Harmonious Relationships in Art and Music is not about artists transitioning. It is about how the three dozen artists represented investigate ways in which the aural and visual constructs of music can inform their art. The artists in this exhibition have taken instruments and concepts of composition and played with them with humor and intellect, some using historical references, some expressing political opinions, many leaving haunting effects.

Mark Applebaum is the solo composer in Sound Vision. Applebaum’s pictographic score, Metaphysics of Notation #6, takes the form of a work on paper filled with dangling symbols and empty spaces. It was not necessarily created as a “pure” work of visual art, but is a musical score that has been uniquely interpreted on many occasions, based on the formal designs of its notation. The inclusion of his work in Sound Vision illustrates how artfully the composer’s mind can work and how skilled the musicians must be to comprehend a score through seemingly random images rather than traditional notation.

Jane Benson’s Pencil (Guitar) works in much the same way. It seems at first glance simply slyly inventive, but has been used to make drawings that have been interpreted by musicians. The instrument thus morphs into the composer. Benson’s musical invention for Song for Sebald is teased from the text of W. G. Sebald’s novel The Rings of Saturn. Benson uses a mat knife to carefully cut away from the text all but the vocal scale (do, re, me, etc.). Each ‘role’ in the novel is then sung with that scale. Benson’s is an intellectual approach that requires a commitment to listening and understanding in much the same way as reading a novel by Henry James does.

Song is incorporated by several other artists in Sound Vision. It provides a partial portrait of Rachel Perry with the presentation of collaged lyrics in her Soundtrack to My Life: All of Me by Billie Holiday. Maureen McCabe brings humor to her Pennies from Heaven as real pennies rain down from the hand of a cherub suspended in a stormy sky. In stark contrast is Whitfield Lovell’s After an Afternoon. Its 37 vintage radios evoke the pre- civil rights era with a soundtrack that includes Billie Holiday singing Yesterdays and Strange Fruit.

Not surprisingly, instruments themselves abound in Sound Vision. Carlos Estevez transforms a clarinet, Soliloquio (Soliloquy), and a violin, Circunloquio (Circumlocution), into marionettes with mournful faces that imply certain tones these instruments might make. Paul Villinski‘s Fable uses a violin spouting butterflies to evoke a light and soothing sound. Kahn & Selesnick inspire the invention of outrageous scenarios in their three works from the Book of Fate Series. What might the Two Fool Cart musicians be playing perched as they are on what looks like an ice flow strewn with red- and white- paper carnations?

On a completely different note, Anita Glesta in Cardiac Harmonium exposes her heart to us, literally, by using the visuals and sounds of her own echocardiogram, mixed with other images and music. Ana Flores also offers an intimate moment with her dancing couple spinning atop a turntable that plays Cuban jazz. Their twirling shadows invoke the nostalgia of memory. These quieter explorations could not be more different in mood from the blasting notes that seem to emanate from the silent canvases of Allan Skirloff’s up-close portraits of jazz musicians.

We all have our personal relationships to music; our individual playlists filled with ideas and tones we are used to. What each of the artists in Sound Vision offers is a perspective on music that in some way startles. There is an alchemy in their ability to take music and make it into art that can give us new insights. Certainly, they provide explorations that we have not undertaken on our own. Will we ever view those playlists in the same way again?

Sound Vision: Harmonious Relationships in Art and Music is supported by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; The Robert Lehman Foundation; the Edith and Herbert Lehman Foundation; the Jarvis and Constance Doctorow Family Foundation; and The New Yankee Stadium Community Benefits Fund. The exhibition will include a 125-page print and online catalogue, published in Mary 2021 by Lehman College/The City University of New York.